It’s not all that common for a White House press briefing to turn into a national debate over the meaning of a 134-year-old sonnet. Yet so it is these days with “The New Colossus,” the immigrant-welcoming poem that’s engraved at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

I’ve always felt that this sonnet is a powerful expression of American exceptionalism. To the Old World we say, “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” These United States, scrappy and egalitarian, will embrace “your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”

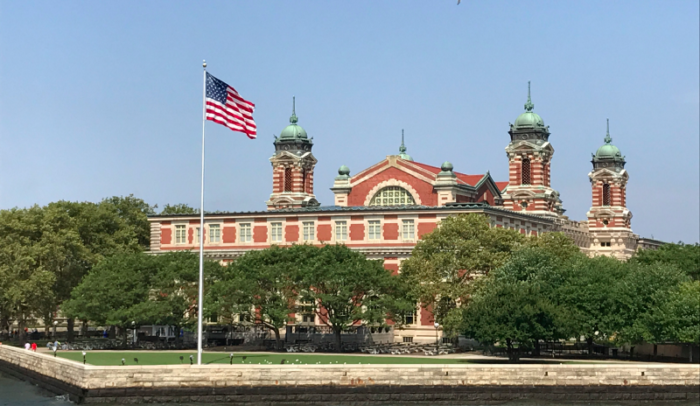

So it seemed like a fitting time for a family trip to Ellis Island, the primary gateway to America for many of the 26 million immigrants who arrived between 1880 and 1924—the largest human migration in history. Situated in New York Harbor just a short ferry ride from Lady Liberty, it’s a remarkably beautiful setting for what was once a complex government bureaucracy:

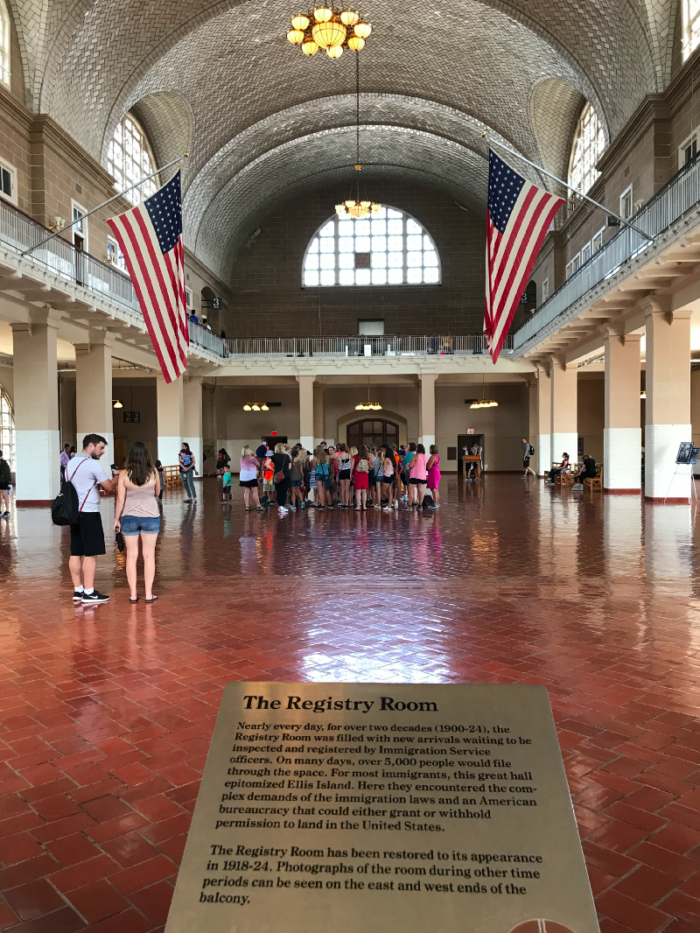

But it was also an efficient bureaucracy, each day processing as many as 5,000 people who spoke over 50 different languages, right here in the great Registry Room:

Today, this building has become our National Museum of Immigration, chronicling the many hurdles these immigrants had to clear in order to make it through Ellis Island and on to their new lives in America.

I was struck by how much has changed — and how much hasn’t. Today, for the one million people each year who are fortunate enough to obtain permanent residency in the United States—also known as a green card—navigating the immigration system takes a lot longer, but retains some distinct similarities to the days of Ellis Island.

Then: A rapid-fire “legal examination” was conducted by an inspector in just a few minutes of intense questioning: “Are you married or single? What is your occupation? Have you ever been convicted of a crime?” About 10% of immigrants then had to plead their case in a special hearing room.

Now: For married couples, the required green card interview with a government officer often delves into their most intimate personal details.

Then: To demonstrate that they wouldn’t become a “public charge,” immigrants cashed in their liras, rubles, and drachmas for just enough dollars to start a new life, often in the home of a relative.

Now: By signing an “Affidavit of Support,”a U.S. sponsor makes a binding commitment to take financial responsibility for an immigrant relative.

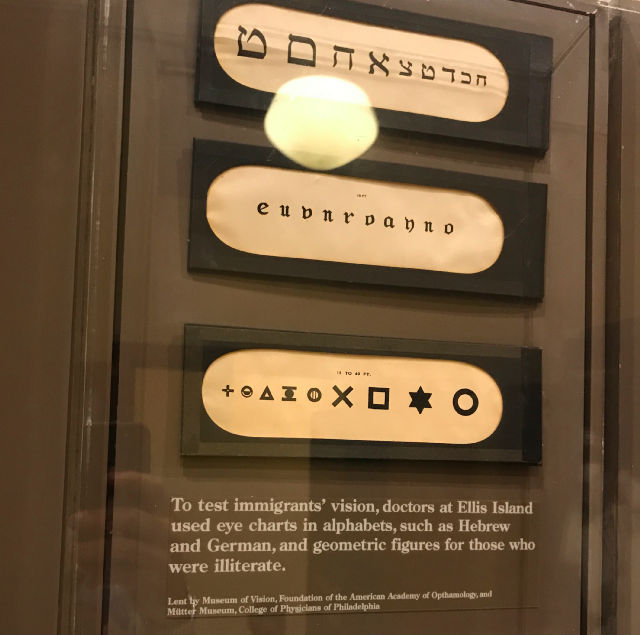

Then: Immigrants filing into the Registry Room had their eyelids propped open for a six-second check for trachoma—a communicable disease that’s easily treatable today but at the time could cause blindness—followed by more tests for anyone who looked pale or tired.

Now: There’s a still a required medical exam, to test for tuberculosis and other conditions of concern, but now it’s conducted in the relatively tranquil setting of a doctor’s office.

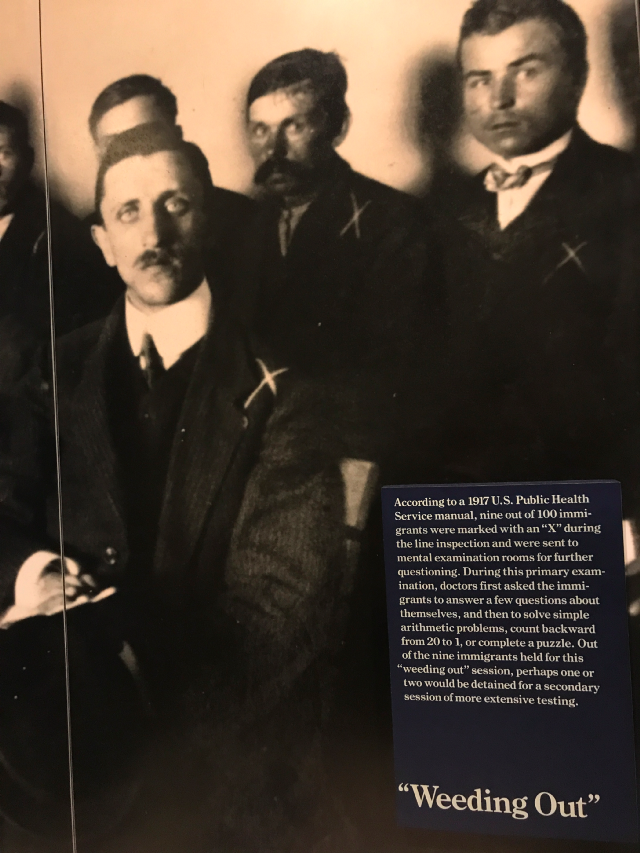

Then: An intelligence test for anyone who seemed lost or confused (but who wouldn’t be, jammed into a room with 5,000 other people fresh off the boat?).

Now: While there’s no longer an IQ test requirement for immigrating to the United States, there’s a lot of debate these days about making our system more “merit-based.”

I’m all for America remaining a beacon for the world’s most talented people—give me your scientists, your entrepreneurs, your brilliant scholars yearning to breathe free!

But let’s be real: There are far more ways to have “merit” than patenting an invention or founding a company, which is why most of us are Americans today. Nearly 40 percent of U.S. citizens can trace their ancestry back to Ellis Island, a rite of passage reserved exclusively for the “huddled masses.” (Immigrants with enough money got to sail straight on to Manhattan.)

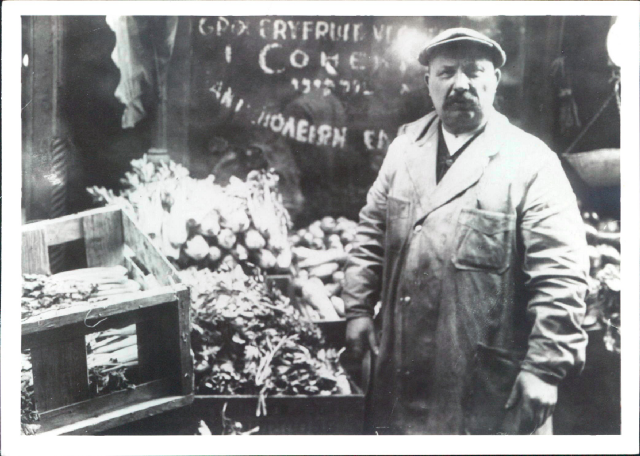

Standing in the great hall at Ellis Island, I reflected on the merits of my great-grandparents, all eight of whom probably passed through that same room a century ago: they were a grocer, a social worker, a peddler, and a farmgirl; a housepainter, a homemaker, a watch repairman, and a seamstress. None of them went to college; none of them spoke much English when they got here.

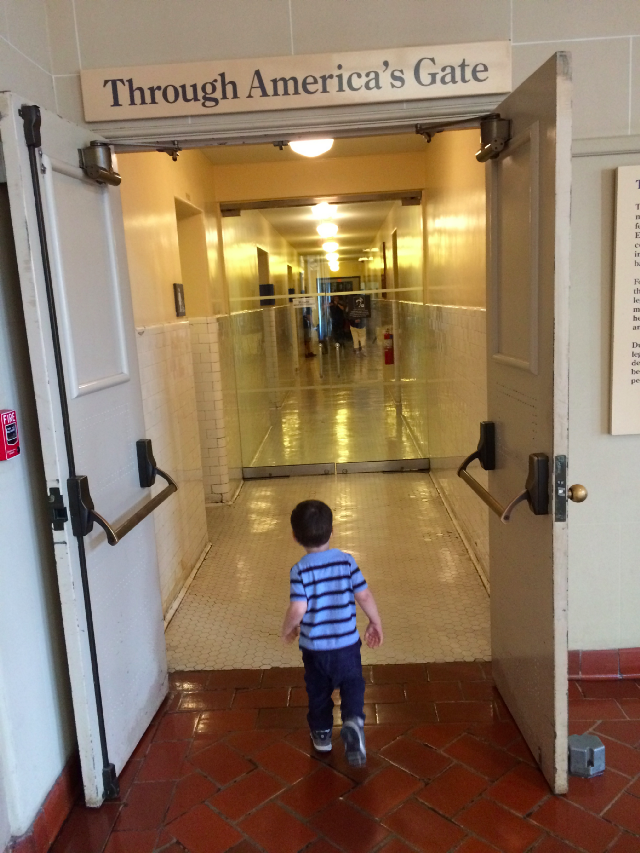

But they did what immigrants do—they got to work, built new lives in a strange country, and imagined a brighter future for their children.

Could they have imagined that I’d be standing here in the same Registry Room today, watching their great-great-grandchildren running around without a care in the world?

The New Colossus

by Emma Lazarus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”